As the CEO of Music Royalty Collection Society Nepal, Ankeeta Shrestha is the official flagbearer for the rights of lyricists and composers in the country. But caught amidst the constant push and pull of media houses and the artists, does the work she does even matter?

On the way to Anamnagar from the northern lane of Singha Durbar, you will pass by a small temple of lord Ganesh on the left. The alley adjacent to it will lead you to a yellow building. Listless, this is where the office of Music Royalty Collection Society Nepal (MRCSN), an organization dedicated to ensure the rights of songwriters and composers, is located.

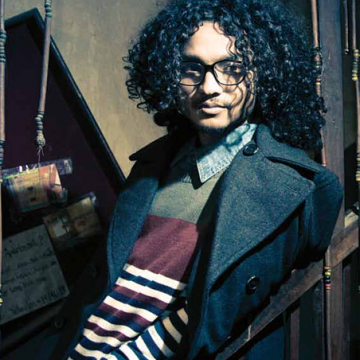

Situated on the south eastern side on the first floor of the building is the desk of Ankeeta Shrestha, CEO of the company. This management is the only eight-year-old CMO (Collective Management Organization), an independent private organisation that works directly under the guidelines of the laws stated by the Copyright Act of the government of Nepal (2002) which administers the rights of songwriters and composers. Its objective is to collect the royalties of the songs that are played in radios, televisions, discotheques, pubs, restaurants and other public places to distribute it to their related composers and songwriters.

To administer its rights, the company suggests musicians and composers to register with them. The second step is making the efforts to convince the various media outlets to obtain a legal license for playing the registered songs. After collecting the royalties, it is distributed to the respective copyright holders. “Amongst the 905 registered members, our company has been successful in distributing a sum of NRs. 4,00,000 to a total of 39 songwriters and 31 composers this year,” Ankeeta declares.

To administer its rights, the company suggests musicians and composers to register with them. The second step is making the efforts to convince the various media outlets to obtain a legal license for playing the registered songs. After collecting the royalties, it is distributed to the respective copyright holders. “Amongst the 905 registered members, our company has been successful in distributing a sum of NRs. 4,00,000 to a total of 39 songwriters and 31 composers this year,” Ankeeta declares.

As spring nears its end, the temperature rises on a hot Kathmandu morning. Ankeeta is already seated at her desk at 9 in the morning. As the CEO of MRCSN, Shrestha manages and facilitates collection as well as distribution of royalties of lyricists and music composers. In addition to managing relations with international agencies and copyright societies as a part of her official responsibilities, she also develops various strategies and programs for the collection of royalties.

“When I came back to Nepal after finishing my MBA with a scholarship from the Indian Embassy, I worked as an intern in two private banks and ended up as an assistant in one,” Ankeeta says. Ankeeta was awarded with three titles in the year 2005 that included Nepal Vidya Bhusan Padak ‘Ga’: conferred by Ministry of Education, Nepal for securing first rank in BBA faculty; Nepal Chhatra Vidya Padak ‘Ka’ by Ministry of Education, Nepal for securing first rank among female students in the BBA faculty and VOITH Sathya Maa Gold Medal from Tribhuwan University for securing first rank in BBA faculty.

“When I applied for the job at MRCSN, I had no expectation of getting it,” Ankeeta says, adding, “Most of the time, my job involves research work on what is happening all around the world regarding copyright laws and trying to implement it here in the local context as much as I can.” As per her agreement with MRCSN, Ankeeta has a few other tasks that the company expects her to perform. Researching usage of musical works locally as well as globally, researching international practices in intellectual property management and applying such findings are some of her many responsibilities.

In other words, Ankeeta is the official flagbearer for the rights of all the lyricists and composers in Nepal. In its working, MRCSN is an almost philanthropic organisation; dedicating its workforce solely for the fight of the rights of lyricists and composers and haggling with the media houses for the collection of royalties. There is, logically, no open slots to question the morality of the organisation.

A case in point was a copyright infringement issue that needed some effort to solve. “Some months ago, a well known lyricist Ratna Sumsher Thapa filed a case against an ad agency for using one of his songs in a popular TVC without his permission,” Ankeeta says. The song was written by him and sung and composed by Narayan Gopal. After arranging several meetings and signing a letter of agreement between both the parties, MRCSN was able to solve the issue as the ad agency agreed to pay compensation to the lyricist and Narayan Gopal Trust. Another case filed under MRCSN was about songs that were being sold illegally by a commercial website without the artist’s permission. The artist, a well known female singer, also the lyricist and composer of the songs had filed a complaint at MRCSN. “We eventually solved the case by taking the help of the CIB (Central Investigation Bureau),” says Shrestha.

In an ideal scenario a CMO, like MRCSN, is appointed by a group of copyright holders to manage issues regarding copyright infringement and royalties. But in Nepal’s case, most artists don’t even know that MRCSN exists. For the sake of safeguarding the rights of the artists, MRCSN has to lure members into their organisation.

In an ideal scenario a CMO, like MRCSN, is appointed by a group of copyright holders to manage issues regarding copyright infringement and royalties. But in Nepal’s case, most artists don’t even know that MRCSN exists. For the sake of safeguarding the rights of the artists, MRCSN has to lure members into their organisation.

I am seated alongside my band manager at the office of a well known online music retailer (the retailer didn’t want to be named) in a nonchalant suburb of Lalitpur to register my band’s second album for legal online download. In front of me is a two pages contract that states the company’s terms and conditions regarding the selling of our music. It says that the band, as a producer, is allowed to work with any other organization, besides an online music retailer up to the five years period of the contract. Fair enough. But then I bring the topic of MRCSN on the table. I wanted to find out where MRCSN stands on the scheme of online music retailers when it comes to paying royalties.

The individual who is dealing with me is visibly agitated at the mere mention of MRCSN. He retorts about the “unfairness” of MRCSN to ask for royalties from them. This had happened a week ago and started with a phone call from Ankeeta’s office, asking for the company’s registration as a legitimate royalty contributor. The online company had declined to be a member of MRCSN as they were themselves paying royalties to the music producers for each songs that were being downloaded by the purchaser.

“How is this logical in any sense when the producers of the music have themselves signed a contract with my company to grant me the rights to sell their music?” he retorts.

Apart from the obvious problem of piracy, MRCSN’s workflow is also hampered by the fact that most major broadcast stations - tv and radio - don’t see the need of MRCSN’s intervention on the matter of artists’ rights. “Besides our 18 registered members that includes Radio Nepal, there are a lot of major TV stations, FM stations, websites and public venues that deny the need to be associated with us,” says Ankeeta, “They are exploiting the creativity of these artists.”

“It’s the fault of the artists of course,” blames Narvottam Ghimire, Membership and Public Relation Officer of MRCSN. He criticises them for being silent when it comes to speaking up for their rights out of fear that the media houses and the public might not play or sell their creations. And this is the general case. Most artists don’t stand up to media houses on the matter regarding the enforcement of their rights and overall royalty collection. And it is not just limited to airplay; musicians have to face the jeopardy of losing their titles for nominations at different music award ceremonies because these award ceremonies are organised by the radio stations itself.

Then there’s the case of the actual amount after royalty is collected. “Previously, in one of the royalty distribution events, some of the senior musicians were pissed off with us for not handing them a notable sum of cash,” says Ankeeta. “Royalty is something that is more of a gesture of respect for one’s creativity rather than earnings.”

Despite all the hassles that challenge the very existence of the sorganisation, Ankeeta has been leading MRCSN, actively being involved on all the matters regarding artists’ rights. A recent achievement of the company has been reaching to an understanding with the state-owned Nepal Telecom to obtain royalties from Caller Ring Back Tone (CRBT). This was in March. According to Shrestha, it took the company several years to convince the company that a part of the hefty sum of cash that the government telecom body earns from their CRBT sales is required to be distributed to the composers and lyricists of the songs.

Gleams of enthusiasm light up Ankeeta’s face when she narrates the case of a protest in India some months ago. It was organised by a mass of musicians who declined providing any songs to the media houses for playing their music unless they received their royalties. But as soon as we land on a topic of the local music scenario, her smile fades. When I asked some unregistered musicians about their views on MRCSN, they were rather skeptical. “Collecting royalty for musicians is something that is not practical in Nepal’s context. Even so, how will that company guarantee that the collected cash will be honestly distributed to the composer and the lyricists with a fair attitude?” a popular artist who wishes to be anonymous shares his cynicism.

Amidst the allegations, Ankeeta and her team keep an eye open for any misdoings, fumble with documents of all sorts, making endless calculations and allocating the royalties for the related individuals who will be handed out their monetary rights each year. Her only wish is that the music scenario of Nepal takes a winding legal and legislative turn.

The author is the lead vocalist of the band Mukut.